ANISH KAPOOR: THE ARTIST IN THE ECHO CHAMBER OF HISTORY

ANISH KAPOOR:

THE ARTIST IN THE ECHO CHAMBER OF HISTORY

WRITING BY

NORMAN ROSENTHAL

‘I will

drench the land with your flowing blood all the way to the mountains.’ (Ezekiel,

32. 6) Form, not color, is generally thought to be the prime aspect of

sculpture. When color is applied as in ancient times to great monuments or,

more recently, in contemporary sculpture in the case of, say, painted steel, it

is still shape and three-dimensionality that give sculpture its essential

identity. For Anish Kapoor, however, color is a fundamental element – essential

to the aesthetic perception of the form. Kapoor’s earliest works, for example

the fragile piles of red, yellow, and blue pigment known as ‘1000 Names’ (1979—1980) – miniaturized

sacred mounds – speak in their essence of the mystical meaning of color. In

this there is some thing of Wassily Kandinsky who, in his famous tract

concerning the spiritual in art from 1912, proclaimed that color “is a

power which directly influences the soul.” [1] But Kandinsky of course was a

painter, not a sculptor.

Kapoor has

made spectacular public works for open air and museum spaces, sensitive to the

site and often on an immense scale. ‘Shooting into the Corner’ (2008–2009),

‘Leviathan’ (2011), and ‘Svayambh’ (2007), the title of which

is Sanskrit for ‘born by itself’ and which consists of a train carriage covered

in blood-red wax moving on tracks through the gallery, are among his most impressive

and shocking sculptures of recent years. In these three works, the turning of

all nature to red is a project of endless possibility, from the savage and the

tortured, to the sublime and the triumphant. Thought of together, they evoke

the powerful poem by Charles Baudelaire, “Le Fontaine du Sang” (1868), from

‘’Les Fleurs du Mal: It seems to me at times my blood flows out in

waves / Like a fountain that gushes in rhythmical sobs. / I hear it clearly,

escaping with long murmurs, / But I feel my body / in vain to find the

wound. Across the city, as in a tournament field, / It courses, making

islands of the paving stones, / Satisfying the thirst of every creature /

And turning the colour of all nature to red.’’ [2]

Kapoor

conveys the inherent symbolic power of color as essence, material, and

readymade. Over the years he has imagined and realized an economy of means in

countless ways, always with an under standing of the necessity to achieve form

that expresses the material’s essence. This says much about his ability to

communicate using, in a fundamentally abstract language, these three elements:

color, form, and material. With these means he achieves a wide range of

sometimes self-evident, but also personal, hidden, and secret meanings. It is

the purpose of this essay to offer clues and connections to a body of work

built up over a period of more than three decades, an endlessly inventive

‘theater of sculpture’ of which this exhibition, Kapoor in Berlin, is a

highly significant stage. Kapoor’s art encompasses the aesthetics of shock and

surprise, but equally that of the sublime and the quiet. It also exemplifies

specific dualities: the pure and the messy; the smooth and the rough; the

void and the dense; the tranquil and the noisy; the implicitly sexual and

the chaste. Often these dualities are present within a single work. Moving

through a large exhibition such as this we find the artist inventing

spectacular pieces onto which we are forced to project and reflect, drawing on

our experience and imagination to interpret the essential forms and colors.

Over the years Kapoor’s evolving work has explored the distinct and inherent

qualities of color – initially the primaries, blue, yellow, red; more recently

he has become happy to explore more complex colors within which to saturate the

viewer. At the same time he has allowed red to occupy a central position in his

oeuvre – as the many works in this exhibition testify, notably the works in

wax. It is a deep, visceral, powerfully associative red color. Kapoor’s wax is

not colored red but is redness embodied. It is also always tending to form – it

never assumes a form that is fixed.

In ‘Symphony

for a Beloved Sun’ (2013), the great environment that dominates

Kapoor’s atrium at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, red wax piles up, as if suggesting

disaster, yet the sun could perhaps be snatching back victory from defeat. Its

title evokes the haunting final line of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, in

which Mrs Alving’s dying syphilitic son Oswald asks, “Mother, give me the sun.”

In this piece Kapoor is, inevitably, challenging the memory of Joseph Beuys

from the legendary exhibition ‘Zeitgeist of 1982’. This was only

the second exhibition in the Martin-Gropius-Bau to take place after its

restoration, following near destruction during World War II – and one which the

author of this essay had the privilege of being a co-curator. Beuys was asked

to occupy the museum’s central atrium.

He chose to

bring with him the entire contents of his Düsseldorf studio – from the work

benches to chairs as well as his individual sculptural tools. Each of these

tools he wrapped in clay to form what he termed the ‘Lehmlinge’. In a part of

the atrium Beuys constructed a six-meter-high Berlin clay mountain, around

which gathered the studio furniture and tools.

Into all

these he had transmuted animalistic spirits. For those willing to enter the

poetics and historical background of the environment it be - came a magical,

even immortal image. Like Beuys, in ‘Symphony for a Beloved Sun’ Kapoor

is attempting to make both a theatrical and sculptural environment of near and

distant resonances, acknowledging the building’s art and historical memories,

and more widely those of Berlin. This new environment of Kapoor’s, with its

rising bands conveying red wax that drops off gradually to build piles on the

floor, resonates with those modernist theatrical productions that took place in

the city in the 1920s and early 1930s. Such stage sets are symbolic of the

cultural and political history of their period – including the good, bad, and

terrifying – yet also suggest a triumph of the sun over the industrialized

bloody mass murders that have emanated, not only out of Berlin, but throughout

the world of the last hundred years and more. Red is the color of blood, the

color of triumph, of love, of the rising sun and its setting. The sun was among

the greatest deities of ancient Egypt – think of the rebel pharaoh, Akhenaten.

Apollo is the all-powerful sun god of Ancient Greece – the god of light, color,

and truth, and the embodiment of art and culture in general.

Sometimes

color is presented as the essence of the form, sometimes it is embedded in a

more pictorial but still essential fashion. Kapoor’s mirrors act like

paintings; their substance and their reflected imagery are one and the same

thing. The silver mirrored piece ‘Vertigo’ (2006),

when situated in an English landscape, becomes as it were, the equivalent of an

English landscape painting by Constable or Turner. We might regard his strategy

as aspiring to hold fast rock or cloud formations in which human faces or

animal forms can be perceived. They could also recall Hermann Rorschach and his

inkblots, which, in psycho logical tests, provide any number of different

responses, consciously or unconsciously expressed. However, where the Rorschach

test has in tended medical application, the perceptual response to a Kapoor sculpture,

regardless of the distance from the artist’s hand, is purely aesthetic.

Kapoor’s work occupies spaces within and without physical and mental space, a

stream of culturally infused visual shocks.

Mirrors as

objects in themselves have accrued an extraordinary cultural history: from

Narcissus onwards, they have functioned as poetic and metaphorical devices,

holding up a mimetic appearance of reality, “Just as it is, unmisted by love or

dislike.”[4] Mirrors, too, when formed as convexes or concaves, or fractured in

endless ways, can arouse astonishing, even miraculous effects that baffle our

initial sense of logic. These senses Kapoor loves to explore for sublime and

sometimes even comic ends. In German literature, the ‘Narrenspiegel’ and the equally famous

character Till Eulenspiegel are long recognized examples of the inherently

comic ‘illusion’ of existence as evidenced by the mystery of the mirror.

All cultures

have seen the essence, even the keys, of creation itself reflected back in the

mirror. In the Newtonian scientific age that has ruled our sense of logic, in

which everything is inherently explicable, explanations nonetheless do not take

away from a sense of surprise when con - front ing re flection effects in

mirrors.

Parabolic

surfaces gather energy and are capable of receiving light and sound in ways

that can be ghostly or energetically expansive, depending on the size and

complexity of each structure. The fascination of the mirror is that it indeed

functions as an echo of the universe. This sense of magic that has resulted

from Kapoor’s play with mirrors achieves a high moment in the spectacular ‘Cloud

Gate’ in Chicago. In such

a cityscape, the reflections might make us recall Vermeer’s painted view of

Delft [ill. 5&6]. Further - more it has become a symbol of the city as much

as the Brandenburg Gate, surmounted by the figure of Victory facing East and

with its own long and complex history, has become the symbol of Berlin.

The complex

engineered beauty of ‘Cloud Gate’, however, through its wondrous parabolic

shape, is that it faces all directions and at the same time none. It creates

the impression of a city as a warped, fluid space – as though each man and

woman becomes a reflection of their own interior landscape – as well as being

suggestive of the male and female sex. Great paintings in the Western tradition

are so often to be perceived as mirrors – the Arnolfini portrait couple,

Velasquez’s ‘Las Meninas’, and Manet’s ‘Bar at the Folies-Bergère’ are all about the ambiguity of

mirrors and the interplay between the imaginary and the real. It is Kapoor’s

particular achievement, in an ongoing series of investigations, to examine

aesthetically the ambiguities of the mirror itself. The mirror, too, can

reflect the sublime, as already suggested. When constructed by Kapoor,

refracting tens of thousands of tiny fragments, all mathematically engineered

into a single concave plane, the viewer fragments as if becoming, for the

glancing moment, a cubist figure shattered almost beyond recognition. In other

cases reversals or inversions take place that seem to defy all logic and common

sense. Confronting again one of his geometrically fragmented monumental

mirrors, the carved 20 ceilings and tiles of the Alhambra come to mind, the intricate

reflected patterns of which could only be created through advanced mathematical

science.

Between the

tenth and the fifteenth centuries, during which time the Alhambra was built,

this knowledge was available to Arab scholars alone – scholars who were able to

project an extraordinary illusion of infinity, suggestive of the autonomous

hand of God, who not only controls but ultimately allows a sense of order, and

wonder, into the world. The aesthetic power of pattern and ornament, translated

into contemporary techniques and insights, plays an equally vital role in the

art of Kapoor.

Ernst

Gombrich in ‘A Sense of Order’ quotes

‘The Seven Lamps of Architecture’ by

Victorian art critic John Ruskin:’there is not a cluster of weeds growing in

any cranny of ruin which has not a beauty in all respects nearly equal, and, in some, immeasurably

superior, to that of the most elaborate sculpture of its stones [i.e. the

sculptural building itself]: and that all our interest in the carved work, our

sense of its richness, though it is tenfold less rich than the knots of grass

beside it; of its delicacy, though it is a thousandfold less delicate ...

results from our consciousness of it being the work of poor, clumsy, toilsome

man.’ [5] Ruskin was

writing in the nineteenth

century, at a moment when the possibilities of the machine to duplicate and make more efficient the work of

man were all too apparent. What he was unable to envisage, however, was the aesthetic

consequences of an artistic practice that does not merely imitate nature – imitation of nature is

something that artists have, in fact, strived for since the beginning of time. Kapoor’s

genius is in devising strategies, inventing machines, or otherwise setting in motion the

conditions of fictive creation that appear to do what nature does, to create the effect not only of

replication but also of its processes, in order to achieve an equivalent of what Ruskin

looked for in his tuft of grass, in a vast rock formation, in a shell, or in a spectacular cave of

stalactites. Each of Kapoor’s works, in a highly calibrated way, appeals to our powers of

abstract and figurative perception. Of course, at one level all art aspires to this, as the

significance of form strives to balance with meaning, and even the great masters of Abstract

Expressionism – Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and so on – were particularly conscious of this

imperative of art. Kapoor – deeply sensitive to cultural history, psychology, and the drive to

metaphor – has a mastery of abstraction based on knowledge and instinct for the

possibilities that lie dormant within the materials

he uses.

In ‘Shooting

into the Corner’ a cannon

fires heavy pellets of red wax into the far corner of a room, making out of the

scattered wax a blood-like stained environment. It is a kind of

threedimensional equivalent of action painting: the work’s final out - come is

unpredictable and the space becomes a noisy battlefield like the drip paintings

of Jackson Pollock, but also in fact like a world of modern violence and

warfare. Materiality and indeed science (Wissenschaft) lie at the heart

of Kapoor’s creative processes. They are part of the wonderment that his art

occasions for those who engage with it – including the artist himself. For

materials, as they submit themselves to the laws of physics in the context of

sculpture, do strange and surprising things; materials behave evermore

paradoxically as they submit to new technologies and new artistic insights. He

plays with a wide repertory of materials: alabaster, earth, steel and other

metals, concrete, wax, and plastics of many different kinds. Young Goethe wrote

in 1776 of a now little-known eighteenth century French Rococo sculptor,

Etienne Maurice Falconet – an artist who could hardly be further away from the

spirit of Kapoor’s world, but who represented for Goethe the transformative

magic of the artist: ‘‘this transparency in the marble which produces the

harmony itself, does it not inspire in the artist

that soft and subtle gradation which he then applies to his own works? Will not

plaster, on the other

hand, deprive him of a source of those harmonies which so enhance painting and sculpture? … No more does

the sculptor look for harmony in his material; rather he puts it there, if he can see it in

nature, and he can see it just as well in plaster as in marble … Why is

nature always beautiful, and beautiful everywhere? And meaningful everywhere?

And eloquent! And with marble and plaster, why do they need such a special

light? Isn’t it because nature is in continual movement, continually created

afresh, and marble, the most lively material, is always dead matter? It can

only be saved from its life lessness by the magic wand of lighting’’.[6]

Falconet, who

originally made models for the Sevres porcelain manufactory, was later

summoned by

Catharine the Great to St. Petersburg to design the statue of Peter the Great,

famous thanks to Pushkin’s poem ‘The Bronze Horseman’. Falconet’s sculpture

became, like Cloud Gate and like the Brandenburg Gate,

the great symbol of a city. ‘A century – and that city young, Gem of the Northern world,

amazing, From gloomy wood and swamp upsprung, Had

risen, in pride and splendour blazing’.[7]

Can momentous

historical events and memories be translated into the category of art without

banality? Once again we can take a clue from Baudelaire, who understood that

art, as well as making any critique or comment, is the glory of expressing what

one dreams, [8] the only way to find a moral equivalent to the realities of

human history, whether through painting or sculpture. Kapoor makes possible a

phenomenal fusion of both, as though they were almost one thing, achieving a

synthesis that balances analysis on one hand and imagination on the other. As

Baudelaire puts it: “Imagination is the queen of truth, and the possible is one of the provinces of

truth. It has a positive relationship with the infinite.”[9]

Kapoor’s hand

is visible in traditional techniques, such as carving and casting, but he also

harnesses technology to make giant sculptures that appear to come about

miraculously, as though by themselves. These can look like ancient cities

uncovered by archaeologists, but now these cement sculptures resemble body

parts of huge, Cyclopean figures come down to us from mythic times. Kapoor,

with out his hand directly involved, yet with his imagination fully in control,

contrives to allow the cement to flow like natural lava, or like meat through a

mincer, producing ever more fantastical shapes. One might describe these

objects as being produced by the hand of God – quite literally the deus ex machina. Some might argue that

a distanced, and alienated, machine is incapable of making an artwork, and that

only the human hand can fashion one, even allowing for accidents of the

‘unfinished’, as perfected by Michelangelo in sculpture and Cezanne in

painting.

But Kapoor’s

concept of the controlled ‘unfinished’ produced by his machine is something new

again, relating to the idea of the autogeneration of the artwork that goes

right back to his early pigment works. In spite of the imperative of discovery

and surprise the Western art world demands, art nonetheless has to act as a

repository of memory, like the Mnemosyne of Greek mythology, who gave birth to

all the nine muses, themselves repositories of memories – historical, cultural,

and scientific. Gombrich, in his biography of Aby Warburg, that famous

constructor of visual cultural memory, quotes his hero, who defines the idea of

‘distance’ or ‘detachment’ as a condition of civilization in art and in

thought: “The conscious creation of distance between the self 26 and the external

world may be called the fundamental act of

civilization.

Where this gap conditions artistic creativity, this awareness of distance can

achieve a lasting social function.”[10] The lasting social function resides

primarily in mental processes, the nuanced ambiguities and ambivalences that

art, relying on our memories, achieves while pushing the game forward. In all

that is produced in Kapoor’s studio, in all the sculpture that before our eyes

appears to generate itself, new possibilities are constantly opening up. The

paradoxically wondrous thing in the case of Anish Kapoor is that each work,

even as it resembles the processes and results of nature and science or as it

automatically self creates, is stylistically identifiable as coming from this

artist alone. ‘Red life burns through my veins, the brown earth

shifts under my feet, with glowing love I hug the trees and the marble

images, which spring to life in my embrace’. [11]

[1] Wassily

Kandinsky, On the Spiritual in Art, Hilla Rebay (ed.), The Solomon R.

Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1946, p. 43.

[2] Charles

Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil, William Aggeler (trans.),

American Library Guild, Fresno, 1954.

[3] Friedrich

Hölderlin, “The Song of a German,” in: Friedrich Holderlin. Poems and

Fragments, Michael Hamburger (trans.), Anvil Poetry Press, London, 2004, pp.

160– 161 / Friedrich Hölderlin, Sämtliche Werke. 6 Bände, Band 2,

Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 1953, pp. 3–4.

[4] Sylvia

Plath, “Mirror” (1961), in: Sylvia Plath, The Collected Poems, Ted Hughes

(ed.), Harper & Row, New York, Cambridge/MA etc., 1981, p. 173.

[5] John

Ruskin, cited in: E. H. Gombrich, A Sense of Order, Phaidon, London, 1979,

p. 39.

[6] Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe, “Commentary on Falconet [Aus Goethes Brieftasche, 1776],”

in: John Gage (ed.), Goethe on Art, University of California Press,

Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1980, p. 17.

[7] Alexander

Pushkin, “The Bronze Horseman,” in: Waclaw Lednicki, Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman,

University of California Press, Berkeley, 1955, p. 140.

[8] Charles

Baudelaire, From the Salon of 1859, Phaidon, London, 1955, p. 231.

9] Ibid., p.

233.

[10] Aby

Warburg, cited in: E. H. Gombrich, Aby Warburg: An Intellectual Biography,

The Warburg Institute, 1970, p. 288.

All the

information writing by Norman Rosenthal and Horst Bredekamp for Anish

Kapoor’s exhibition which had taken by Martin Gropius Bau’s Press Office. You

may visit Anish Kapoor’s Exhibition at Martin Gropius Bau to click below link.

http://mymagicalattic.blogspot.com.tr/2013/09/anish-kapoor-at-martin-gropius-bau-in.html

SVAYAMBH 2012

Installation View From Royal Academy of Arts 2012

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

TALL TREE AND THE EYE AT ROYAL ACADEMY 2012

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

TALL TREE AND THE EYE AT ROYAL ACADEMY 2012

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

MY RED HOMELAND 2003

Wax, Steel, Motor, Oil Based Paint

Courtesy the Artist Museum

of Contemporary Art Australia

© Anish Kapoor

MY RED HOMELAND 2003

Wax, Steel, Motor, Oil Based Paint

Courtesy the Artist Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

© Anish Kapoor

MY RED HOMELAND 2003

Wax, Steel, Motor, Oil Based Paint

Courtesy the Artist Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

© Anish Kapoor

MEMORY 2008

Cor – Ten Steel

Dimensions: 4.48×8.97×14.5

m

Deutsche Bank and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Foundation

Courtesy the Artist Museum

of Contemporary Art Australia

© Anish Kapoor

MARSYAS 2002

View From Tate Modern Turbine Hall

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

MARSYAS 2002

View From Tate Modern Turbine Hall

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

CLOUD GATE 2004

View From Millenium Park Chicago

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

CLOUD GATE 2004

View From Millenium Park Chicago

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

SYMPHONY FOR A BELOWED SUN 2013

Mixed Media - Dimensions Variable

Installation View: Martin-Gropius-Bau, 2013

Courtesy the Artist

© Anish Kapoor / VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2013

SYMPHONY FOR A BELOWED SUN 2013

Mixed Media - Dimensions Variable

Installation View: Martin-Gropius-Bau, 2013

Courtesy the Artist

© Anish Kapoor / VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2013

SHOOTING INTO THE CORNER 2008-2009

Mixed Media - Dimensions Variable

Photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn

© Anish Kapoor / VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2013

UNTITLED 2010

Wax, Oil Based Paint and Steel

Dimensions: 135.5 x 135.5 x 222.5 cm

Installation view: Pinchuk Art Centre, Kiev, 2010

© Anish Kapoor / VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2013

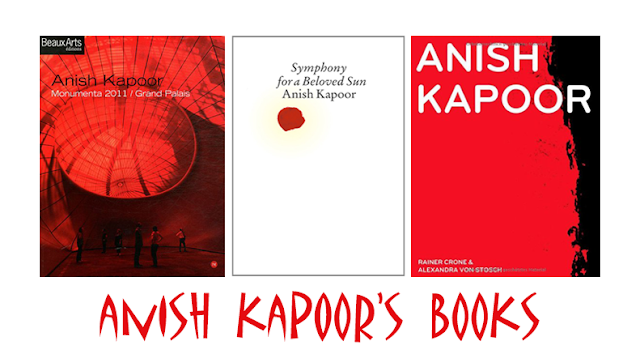

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT

a) Non-Object (Oval Twist), 2013

Stainless Steel

Dimensions: 250 x 128 x 150 cm

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

b) Non-Object (Door), 2008

Stainless Steel

Dimensions: 281.3 x 118.1 x 118.1 cm

Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

c) Non-Object (Square Twist), 2013

Stainless Steel

Dimensions: 250 X 144 X 100 cm

Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery

Installation view: Martin-Gropius-Bau, 2013

Photo: Jens Ziehe

© Anish Kapoor / VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2013

LEVIATHAN AT GRAND PALAIS 2011

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

THE DEATH OF

LEVIATHAN: FORM AS A POLITICAL ISSUE

THE

WILLFULNESS OF THE FORM

WRITING BY

HORST BREDEKAMP

The Death of

Leviathan stands at the

end of a series of works in which art theory and the theory of the state were

interlocked in a peculiar way. But for Anish Kapoor, what counts first is form.

Taking up the ambition of Minimal Art and Concept Art, the furthest thing from

his mind is an art that offers itself to the viewer. He follows the line

tracing back to Wilhelm Worringer’s 1907 dissertation Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy), which

propounded a counter-position to the philosophical and psychological doctrine

of empathy. [1] A work whose eye

is on its audience from the beginning cannot reach this audience in its inner

most, while an art that initially follows its own logic is able to unfold a

fascinating interplay with the recipient.

This doctrine

opposes all theories that tie visual art to a representing function in the

sense of imitating nature, feelings, or the political realm. Kapoor has

developed this counter-principle in his works through their Euclidean geometry,

surrealistic coloration, unexpected tearing open of spaces, and aseptic,

immaculate mirrors. To be able to be present, the works must first withdraw

into their own spheres of absoluteness. This inner constancy, which expresses

itself in rejecting any narration, fixed halting point, or proportional

reference, conveys the prelude to a deeper relationship. Kapoor’s pyramids and

spirals, and especially the huge concave mirrors embedded in stone steles that

produce an upside-down mirror image, [2] embody a principle through which works

that initially aesthetically withdraw make a stronger impression than those

which ingratiate themselves, dripping with insinuated

meaning, into

the viewer’s horizon of willing expectations.

This is not

the conciliatory form of the sublime formulated by Kant, but Edmund Burke’s

more painful variant of unbridgeability that induces people, faced with

unboundedness, to find guiding principles in themselves. This also led Barnett

Newman to follow Burke instead of Kant. [3] This is about the intensified

addressing that can arise after distance is taken. Because all great

spaciousness bears the danger of an inner sterility, grand dimensions, which

may seem to suggest themselves for this interplay, are initially unsuitable.

Kapoor has

taken on the challenge of precisely this problem in his large-format works,

notably in ‘Memory’ 2008, and in ‘Leviathan’ 2011. In ‘Memory’, exhibited in

the Deutsches Guggenheim, Berlin, the boundary between sculpture and

architecture is crossed; but the unboundedness is bound by the fact that the

surface shows a patina of rust, which, comparable to a fine pigment, surrounds

the object like the paint of a painting.

The rough

variegation of this surface lends the huge, traversable form an organic

character that takes away the steely quality of its hull [ill. 2].

Added to this

is that the unsurveyability of the whole relies on the processual remembering

of the participant who moves through the ensemble; this is why Kapoor calls Memory a “mind sculpture.”[4] The vast

dimensions of this architectural sculpture initially seem to both repel and

subsume the viewer; its organic appearance gives it a pulsation that makes it a

seemingly living organ; and the forced act of memory leads to the freedom of a

mental sculpture put together from memory again and again, a sculpture whose

inner dynamic contradicts its rigid alien quality.

This

principle corresponds to a currently widespread approach that questions the

hypertrophy of the modern subjective

individual. Here it is a question of confronting something that, although it is

a human artifact, refuses function. Striving to understand the implicit person as part of an environment

confronting him[5] is on a level similar to attempting to recognize an intrinsic value

in objects, which should lead

metaphorically to a parliament of

objects [6] or to seeing

in the willful quality of artifacts the effect of a pictorial act. Kapoor’s works are embodiments of what

can be called an intrinsic

pictorial act.[7]

Resin, Air

Space, 1998, gave this principle an early programmatic turn: suspended within

the space of the minimalistically clear stereometry of a transparent block is a

Something that does not entirely tally with the defined hardness of its

boundaries.

It would be

banal to speak here of the soul of an object, but the inner life of this form

testifies at least to the idea of a latency of what is inorganically formed

that does not entirely tally with viewers’ expectations.

Kapoor

formulated this paradigmatically in his work ‘When I am Pregnant’, made in the early 1990s, in which

a bulge presses out of the veraicon of the white surface of the

wall . Something similar played out with the Leviathan of the Grand Palais in 2011.

The

monumental character of this sculpture-architecture was boundless, like that of Memory, but here, too, the artist knew

how to create the quality of a living organism. A huge, pictorially active

art-animal that, in the latency of its lurking appearance and the

metamorphosing play of light in its ambience, also overcame the emptiness that

can accompany monumentality.[8]

THE

RELATIONSHIP TO POLITICAL ICONOLOGY

It is

possible that a wordless presence would have left the work more freedom than

titling it Leviathan permits. On the other hand,

precisely this suggestive title opens up the broad field of political iconology

and the specific way Kapoor has dealt with it.

With Thomas

Hobbes’ Leviathan, Kapoor refers

explicitly to the work that founded the modern theory of the state. Hobbes, in

turn, referred to the two monsters in the Bible that demonstrate God’s sublime

power to the rebelling Job: Leviathan and Behemoth. These two creatures, before

which “terror dances,”[9] appear as the monsters of the sea and land. [10] In

his frontispiece, Hobbes has converted Leviathan into the form of a humanoid

giant rising out of the sea.[11]

But Kapoor

retracts this transformation. He confronts the image of the state developed by

Hobbes with the counter-model of a semi-organic being that displays no human

traits.

He sought to

avoid the humanoid machine as which Hobbes interpreted his Leviathan as a metaphor of the state.

[12] Kapoor’s Leviathan thus belongs to the realm of

the counterimages that present alternatives to Hobbes’ state-animal that, with

relentless violence, suppresses people’s bloodlust to create a repressive

peace. [13] Nor has Kapoor conformed to William Blake’s famous version of the

two monsters from the Book of Job. In Blake’s image, Behemoth appears in the

upper half of the globe of the world like a kind of monstrous hippopotamus,

while below it Leviathanroils as a dragon in the sea. [14]

Kapoor’s Leviathan, by contrast, with its

softly contoured huge form, is more in keeping with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, which, in accordance with a

long tradition, imagined Leviathan as a whale. [15] In his introduction,

Melville quoted Hobbes’ Leviathan:

“By art is created that great Leviathan called a Commonwealth or State – (in

Latin, Civitas) which is but an artificial man.”[16] Because Melville cites

Hobbes literally, the impression could arise that his whaling novel was to be

grasped as a parable of the struggle against the Hobbesian state, and this

interpretation had a powerful and in part dreadful effect.

In March

1969, a militantly anti-capitalistic oppositional group appeared in the United

States; with its magazine Leviathan,

it sought to accompany the struggle against the state, regarded as a whale. In

November 1969, it published an editorial titled “from the belly of the whale”

that tied Melville’s novel to the Old Testament story of Jonah. The people,

swallowed by the state as whale, should slash open the state from the inside:

“We began life as Jonah, as a part of a movement trapped inside the belly of

the great whale that devours us all. We’re still not sure exactly what that

whale looks like, exactly how to get out: but what we do know is that we’re not

going to be passengers anymore. We’re going to learn how to rip that whale’s

gut apart.”[17] On one of the covers of the magazine Leviathan, the state-whale appears as

a caricature of a sea monster equipped with three torsos and heads [ill.

7].[18] The right-hand

head has a

trunk and embodies capital, while the monster on the left, armed with pistols,

represents the police. Both protect the bespectacled figure in the middle that

is filling a test tube while looking ahead and setting the course. The

Leviathan appears as a monstrous triad of the organic interplay between

capital, police power, and research.

A trail may

lead from this identification of the Leviathan as a whale that must be

combatted to the German terrorist group, the RAF (Rote Armee Fraktion = Red Army Faction), which also

assumed that Melville’s Moby Dick alluded to the state. Almost all the

members of the RAF took cover names out of the novel.[19]

Melville’s

reversion of Hobbes’ humanoid Leviathan back to the sea-monster form in which

it appeared in the Old Testament also impacted the political milieu that did

not promote but criticized or even castigated the destruction of the state

animal. Thus, in his 1938 settling of scores with the criticism of Hobbes’ Leviathan, Carl Schmitt said that

liberalism had “slain and eviscerated” the modern state. [20] The cover of the

1982 reprint of Schmitt’s book took up Melville’s identification of the state

with the whale, against Hobbes’ imagery: Hendrick Goltzius’ engraving Beached Whale, in which men are

beginning to eviscerate a dead whale, is the cover illustration.[21]

Following the

criteria of political iconography, Kapoor’s transformation of Hobbes’ humanoid

pictorial metaphor for the state into a huge, artificial organism stands in the

same tradition. This is the starting point for the problematic mentioned at the

beginning. To start with, a comparison between the three-headed monster of the Leviathan of March 1969 and Kapoor’s Leviathan from 2011, with its three bulges

like an abstract implementation of this fantasy, may urge itself upon us [ill.

9]. But here Kapoor was interested in a problem of form and not in giving

visual expression to three bodies of state terror, as the caricature wanted to.

Iconographically, all that remains is the common reference to Melville’s

transformation of the state giant into a sea monster.

Despite its

distance from Hobbes’ image of the state, Kapoor’s Leviathan is closer to the concept of the

Leviathan than to Hobbes’ critics. He shows the Leviathan in its sub lime

vastness as a doublecreature: alien and uncanny, and yet attractive and

alluring in its organic presence.

This is where

the artphilosophical and the statetheoretical components touch each other. The

Leviathan appears as a huge amorphous sculpture that subsumes the viewer and

yet drives him to an extreme activity of empathy and reflection. In this, it is

an example of pictorial activity coming toward one from alienness and also of

the problematic and achievement of the state: always in danger of consuming

one, it is nonetheless a lively and life-enabling counterpart.

THE DEATH OF

LEVIATHAN

The Death of

Leviathan leaves this

dialectic behind. The huge animal lying on the ground corresponds with the idea

that the state has lost its justification for existence since the 1990s

because, in the face of the dissolution of the Iron Curtain between the blocs

and the fact that just one form of economics enables global networking and

connection, people could now associate freely. They dictate the laws to the

state, and not the reverse: this was the doctrine considered valid until 2008,

when the horrendous consequences of the receding of the state became

obvious.[22]

The Death of

Leviathan could symbolize

this process, and with that its message would be much more open politically

than all of Kapoor’s earlier works. In this sense, ‘The Death of Leviathan’ makes the prediction that the future

of society free of the state, whether hoped for or lamented, has already begun.

That the condition of a failed state in no way means a liberated anarchy, but

rather terror and the abuse of power, becomes clear in the face of the pitiable

horror of this dying sculpture. Accordingly, a more fitting title than ‘The

Death of Leviathan’ might be ‘Behemoth’, the second

monster from the Book of Job, with which Hobbes identified the unending civil

war that would accompany the collapse of the state.[23] The sculpture assumes

the prophetic role of Cassandra: it explains the currently unfolding,

desperately conflictual efforts to bring under state control the processes of

global finance and

the economy,

as well as the ongoing latent and open civil wars as a snapshot of a grand iose

failure. From the perspective of political iconology, ‘The Death of Leviathan’ offers no wayout, but confronts

the recipient with the message that he should prepare for a situation of

intractability.

And with

that, the form comes back to itself. It is the indefatigable work on the

material that becomes clearer in the moment of failure than ever before. No

reconciliation lies in this, but the return of the principle of arguing from

distance and of regarding art as a counterpart that makes its own demands,

which are uncontrollable but precisely for that reason can be judged and

evaluated. Via the form, art encompasses all areas of life, together with the

political realm.

[1] Wilhelm

Worringer, Abstraction and

Empathy. A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, Routledge and Kegan Paul,

London, 1967.

[2] On this

motif, cf. especially: Anish Kapoor, Turning

the World Upside Down, exhib. cat., Kensington Gardens, London, Verlag der

Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne, 2010.

[3] Barnett

Newman, “The Sublime is Now,” in: Tiger’s

Eye 6, 15 December 1948, p. 52–

53; cf. Max Imdahl, “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III,” in: Christine

Pries (ed.), Das Erhabene.

Zwischen Grenzerfahrung und Größenwahn, VCH, Weinheim, 1989, pp. 233–252, here:

p. 235.

[4] On this,

cf. the unpublished study: Anna Katharina Groth, Anish Kapoors Auftragsarbeit Memory

(2008): Ein Objekt zwischen Skulptur, Bild und Bauwerk, Magisterarbeit,

Institut für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2010.

[5] Wolfram

Hogrebe, Der implizite Mensch,

Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2013.

[6] Bruno

Latour, Das Parlament der Dinge. Für eine politische Ökologie, Suhrkamp

Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2010.

[7] Horst

Bredekamp, Theorie des Bildakts.

Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 2007, Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2010.

[8] Monumenta 2011: Anish Kapoor/

Leviathan / Grand Palais, exhib. cat., Réunion des Musées Nationaux Grand

Palais, Paris, 2011, No. 112.

[9] Job

41:22, in: New Revised Standard

Version Bible, 1989.

[10] Job

40:15–41:26.

[11] Thomas

Hobbes, Leviathan, London, 1651:

frontispiece. Cf. Horst Bredekamp, Thomas

Hobbes. Visuelle Strategien. Der Leviathan:

Urbild des modernen Staates. Werkillustrationen und Portraits, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 1999. Cf. idem,

“Thomas Hobbes’s Visual Strategies,” in: Patricia

Springborg

(ed.), The Cambridge Companion to

Hobbes’s Leviathan,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2007, pp. 29–60.

[12]

“Introduction” in: Richard Tuck (ed.), Thomas

Hobbes: Leviathan, Cambridge Uni - versity Press, Cambridge, 1991 [1651], p. 9.

[13] Horst

Bredekamp, Thomas Hobbes. Der

Leviathan. Das Urbild des modernen Staates und seine Gegenbilder 1651-2001,

Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 2012 (4 ed.), pp. 132–139. Cf. Dario Gamboni,

“Composing the Body Politic. Composite Images and Political Representation,

1651-2004,” in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (eds.), Making Things Public. Atmospheres of Democracy, exhib. cat., ZKM |

Karlsruhe, MIT, Cambridge/MA, 2005, pp. 162–195.

[14] Bo

Lindberg, “William Blake’s Illus tra - tions to the Book of Job,” in: Acta Academiae Abonensis, No. 15 D,

1973, p. 299.

[15] On this

tradition: Noel Malcolm, “The Name and Nature of Leviathan: Political Symbolism

and Biblical Exegesis,” in: Intellectual

History Review, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2007, pp. 21–39, here: p. 28.

[16] Thomas

Hobbes, cited in : Herman Melville, Moby-Dick,

or: The Whale, Constable

and

Company,

London, Bombay and Sydney, 1922, p. XV.

[17] Leviathan, Vol. 1, No. 6, November

1969, p. 3.

[18] The

imprint gives no indication of the artist, who signed simply with “mack” (Leviathan,

Vol. 1, No. 1, March 1969).

[19] Stefan

Aust, Der Baader-Meinhof- Komplex,

Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1986, pp. 274–277. Cf. idem, “Wer die RAF verstehen

will, muß ‘Moby Dick’ lesen. Vor dem Deutschen Herbst: Ein Gespräch mit Stefan

Aust, dem Autor des Klassikers ‘Der Baader Meinhof Komplex’,” in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 22

August 2007, No. 194, p. 31.

[20] Carl

Schmitt, Der Leviathan in der

Staatslehre des Thomas Hobbes. Sinn und Fehlschlag eines politischen Symbols,

Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg, 1938, p. 124.

[21] Günter

Maschke (ed.), Carl Schmitt, Der

Leviathan in der Staatslehre des Thomas Hobbes. Sinn und Fehlschlag eines

politischen Symbols, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, 1982.

[22] Martin

van Creveld, Aufstieg und

Untergang des Staates, Gerling Akademie Verlag, Munich, 1999; Reinhard

Wolfgang, Geschichte der

Staatsgewalt. Eine vergleichende Verfassungsgeschichte Europas von den Anfängen

bis zur Gegenwart, C. H. Beck, Munich, 1999. An excellent overview is offered

by Mario G. Losano, “Der nationale Staat zwischen Regionalisierung und

Globalisierung,” in: Jörg Huber (ed.), Darstellung:

Korrespondenz, Voldemeer, Zurich, 2000, pp. 187–213. [23] Horst

Bredekamp,

“Behemoth als Partner und Feind des Leviathan. Zur politischen Ikonologie eines

Monstrums,” in: Leviathan, Vol.

37, 2009, pp.

429–475 (also as offprint: TranState

Working Papers, No. 98, Bremen: Sfb 597 “Staatlichkeit im Wandel,” 2009.

Reprinted in:

Philip Manow, Friedbert W. Rüb, and Dagmar Somin (eds.), Die Bilder des Leviathan. Eine

Deutungsgeschichte, Nomos, Baden-Baden

LEVIATHAN AT GRAND PALAIS 2011

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

UNTITLED ( RED DISH ) 2011

Resin & Fiberglass

Dimensions: 135 cm Diameter

Resin & Fiberglass

Dimensions: 135 cm Diameter

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

FLOATING DAWN 2011

20 Acrylic Cubes in 2 Lines of 10

Dimensions: 35 x 28 x 28 cm Each

20 Acrylic Cubes in 2 Lines of 10

Dimensions: 35 x 28 x 28 cm Each

Exhibition view “Anish Kapoor & James Lee Byars”, Kamel

Mennour

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

FLOATING DAWN 2011

20 Acrylic Cubes in 2 Lines of 10

Dimensions: 35 x 28 x 28 cm Each

20 Acrylic Cubes in 2 Lines of 10

Dimensions: 35 x 28 x 28 cm Each

Exhibition view “Anish Kapoor & James Lee Byars”, Kamel Mennour

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

DETAIL 2010

Cement

Variable Dimensions.

Variable Dimensions.

Exhibition view at the Chapelle des Petits-Augustins of the

École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux - Arts, Paris, 2011

Photo. Fabrice Seixas © Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

COSMOBIOLOGY 2013

Resin

Dimensions: 126 x 128 x 500 cm

Resin

Dimensions: 126 x 128 x 500 cm

Exhibition View “Anish Kapoor & James Lee Byars”,

Galerie Kamel Mennour

Photo: Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

Photo: Fabrice Seixas © ADAGP Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris

THE ARCELOR MITTAL ORBIT 2012 FOR LONDON OLYMPICS

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

THE ARCELOR MITTAL ORBIT 2012 FOR LONDON OLYMPICS

Courtesy the Artist © Anish Kapoor

WIDOW 2004

PVC-poliestere, acciaio

Dimensions: 4610 x 14630 x 4610 cm

©Fondazione MAXXI © Anish Kapoor

PVC-poliestere, acciaio

Dimensions: 4610 x 14630 x 4610 cm

©Fondazione MAXXI © Anish Kapoor

CAVE 2012

Corten

Corten

Dimensions: 551

x 800 x 805 cm

Courtesy the Artist and Galleria Continua

© Anish Kapoor

THE EARTH 2012

Courtesy the Artist and Galleria Continua

© Anish Kapoor

INTERSECTION 2012

Corten

Dimensions: 515

x 812,5 x 514,4 cm

Courtesy the Artist and Galleria Continua

© Anish Kapoor

INTERSECTION 2012

Corten

Dimensions: 515 x 812,5 x 514,4 cm

Courtesy the Artist and Galleria Continua

© Anish Kapoor

WHEN I AM PREGNANT 1992

Fibreglass, Wood and Paint

Dimensions: 180.5×180.5×43cm

© Anish Kapoor

SLUG 2012 - 2013

Paint and Fiber Glass

Dimensions: 415 x 600 x 465 cm

Paint and Fiber Glass

Dimensions: 415 x 600 x 465 cm

© Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and De Pont Museum

Courtesy the Artist and De Pont Museum

VERTIGO 2012

© Anish Kapoor

Courtesy the Artist and De Pont Museum

DIRTY CORNER 2010

Fabbrica del Vapore, Milano

© Anish Kapoor

ANISH KAPOOR

12 March 1954

Born in Mumbai, India. Kapoor spends his childhood in Mumbai

and his youth

at the well-known boarding school The Doon School in

Dehradun.

1970–1973 At

the age of 16, he moves to Israel to live on a kibbutz. After

six months he

quits his studies of electrical engineering and decides to become an artist. He

soon attains international renown with his sculptures made of pigments.

1973 Travels

to the UK to study at the Hornsey College of Art in London and then

at the Chelsea College of Art and Design.

1979 Teaches

at the Wolverhampton Polytechnic in the U.K. That same year, he

travels to India, where he is enchanted by the vibrant powdered pigments he

sees everywhere, from temples to market stands. He soon begins to create

sculptures coated with colour-saturated pigments.

1982 Becomes

Artist in Residence at the Walker Art Gallery in

Liverpool and later exhibits at the Lisson Gallery in London. He is

part of the movement that would later become famous as New British Sculpture.

1990 Represents

Britain in the Biennale in Venice, and in 1992 in documenta IX in Kassel.

1991 Awarded

the Turner Prize.

1996 Creates

an altar of black Irish limestone for the Frauenkirche in Dresden; the altar is

located in the lowest point of the church, at the apex of the cruciform barrel

vault.

2002 The

installation Marsyas is displayed in Tate Modern’s türbine

hall in London.

2003 The

Kunsthaus Bregenz exhibits My Red Homeland, a 20-tonne sculpture of red

vaseline and wax Press kit: Kapoor in Berlin page 6

2004 Anish

Kapoor creates the installation Cloud Gate at the Millennium Park

in Chicago, a monumental 110-tonne polished stainless steel sculpture.

2008

Conceptualizes the steel sculpture Memory for the Deutsche

Guggenheim, Berlin.

2009 Presents

the installation Shooting into the Corner at the Museum für

Angewandte Kunst (MAK) in Vienna. That same year, the Royal Academy in London

devotes an extensive solo exhibition to Kapoor.

2011 His work

Leviathan is exhibited at the Grand Palais in Paris as part of the

annual Monumenta. Works by Kapoor are on display simultaneously at two

exhibition venues in Milan: the Rotonda di Via Besana and the Fabbrica del

Vapore. In October, Kapoor is awarded the Praemium Imperiale in Tokyo.

2012 On the

occasion of the London Olympics, Kapoor creates the

Arcelor

Mittal Orbit, a tower 115 metres high.

Anish Kapoor

is a member of the Royal Academy and a Commander of the British

Empire (CBE).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)